The brain can be trained to prefer healthy food over unhealthy high-calorie foods, using a diet which does not leave people hungry,” reports BBC News.

It reports on a small pilot study involving 13 overweight and obesepeople who, aside from their weight, were described as being in good health.

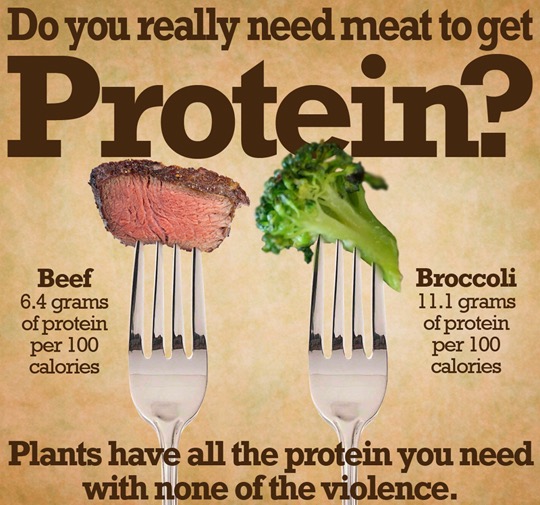

Researchers looked at whether a dietary weight loss programme, known as the iDiet, could change how the brain’s reward system responds to high- and low-calorie foods. The iDiet included carbohydrates that released glucose slowly into the bloodstream (a low glycaemic index), and higher fibre and protein. It also aimed to reduce calorie intake by 500 calories (kcal), to 1,000kcal per day.

Adults on the iDiet lost more weight than those not on the diet. Interestingly, MRI scans suggested that their brains had increased the “reward” in response to anticipation of eating low-calorie foods and reduced the “reward” response to high-calorie foods compared to people not on the plan.

People can change their eating habits, which can lead to sustainable weight loss. This study supports this notion, and suggests that part of this may be related to changes in our brain’s “reward” response. The researchers hope to use this knowledge to improve weight loss interventions, but as yet it is not clear whether this will become a reality.

Where did the story come from?

The study was carried out by researchers from Harvard Medical School and other research centres in the US. It was funded by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging. One of the authors reported that she was the co-founder of a commercial weight loss programme (the iDiet) based on the approach described in the research paper.

The study was published in the peer-reviewed journal Nutrition & Diabetes, and has been made available on an open-access basis so it is free to read online.

The UK media has covered this research in a reasonable way. Both the Mail Online and BBC include comments from the lead researcher, noting that “there is much more research to be done here, involving many more participants, long-term follow-up and investigating more areas of the brain”.

What kind of research was this?

This was a randomised controlled trial, testing whether a new weight loss programme could change how the brain’s reward system responds to healthy and unhealthy food.

We need food to survive, but it takes effort to find and prepare food, so the brain “rewards” us for doing these tasks in anticipation of eating, by increasing levels of chemicals such as dopamine inside our brains.

This reward reinforces this behaviour. High-calorie foods provide more reward than lower-calorie foods, and this can cause people to choose these foods in preference to healthier options.

Reinforcement of this behaviour by the brain’s reward system may contribute to over-eating of these foods and, ultimately, obesity. The researchers say whether the brain can be trained to reverse this through a behavioural weight loss intervention, and therefore help to treat obesity, is not known. Two previous randomised control trials had found no impact of a weight loss programme on the brain’s reward system.

A randomised control trial is the best way to test the impact of an intervention on a given outcome. This was a pilot study, which means that it was a small-scale test to get some initial idea of whether the intervention works. If initial signs are positive, this would be followed up by a larger study to confirm these initial findings.

What did the research involve?

The researchers included 15 overweight or obese adults who were otherwise healthy and who were taking part in a larger randomised control trial of a weight loss programme called the “iDiet” in their workplaces. They had brain scans before and six months into the programme to see if the reward system in their brains had changed its response to the anticipation of high-calorie and low-calorie food.

Participants were randomly allocated to either the iDiet or no weight loss intervention for six months. The iDiet aimed to help people to lose 0.5 to 1kg per week in a sustainable way. Participants took part in group sessions that aimed to get them to reduce calorie intake by 500-1,000kcal per day (roughly the calorie content of a large takeaway cheeseburger).

They received weekly hour-long sessions for 15 weeks, followed by fortnightly sessions for eight weeks.

The iDiet included elements aimed at reducing hunger and reducing existing associations between unhealthy food and reward, while reinforcing associations between healthy food and reward. The researchers provided portion-controlled menus and recipes that combined low glycaemic index carbohydrates (providing about 50% of the diet’s energy) with higher fibre (40g/day or more) and protein (about 25% of energy from protein and fat). There were also specific low-calorie “free foods” that could be eaten as desired. This combination aimed to make participants feel fuller and reduce hunger.

The researchers had specific criteria for people to be eligible to take part in the brain scanning part of the study (for example, they could not have had any psychiatric problems in the last two years). It was not clear from the reporting exactly how many people in total were in the randomised control trial and how many in total were eligible for the brain scan part of the study.

Of the 15 people who enrolled in the brain scan study, two dropped out – one lost their job and one felt claustrophobic in the brain scanner. Eight of the remaining participants were in the iDiet group, and five were in the control group.

The study used a type of brain scan called a functional MRI (fMRI), which detects activity in different parts of the brain. The researchers were particularly interested in the part of the brain called the striatum, as this has been reported to be involved in giving “rewards”. The participants were shown 40 images of commonly eaten high-calorie and low-calorie foods while they were in the scanner, to see how their brains responded. The participants also rated each food from one (not desirable at all) to four (extremely desirable).

They were also shown non-food images so that the researchers could take into account how active the brain regions normally were when not exposed to food. The brain scans were taken four hours after a meal, so about when the participants would be ready for another meal.

What were the basic results?

Participants on the iDiet lost 6.3kg on average over six months, while the control group gained 2.1kg. It was not clear whether these results were for the entire randomised control trial, or just those participants taking part in the brain scan part of the study.

Compared to the control group, the iDiet participants showed greater increase in activation of one part of the striatum (a reward-related brain region) when shown low-calorie foods, and more reduction in activation of another part of the striatum when shown high-calorie food after six months. Other parts of the striatum that had previously been implicated in the food reward system did not show differences between the groups.

The iDiet participants reported a greater increase in desirability of the low-calorie foods, and a greater reduction in the desirability of the high-calorie foods than the control group. However, this difference was not large enough to reach statistical significance.

The changes over time in brain response did not appear to show a relationship to changes in eating behaviour in the eight iDiet participants.

How did the researchers interpret the results?

The researchers concluded that this was the first randomised control trial to show changes in the brain reward system response to high- and low-calorie foods in response to a weight loss programme. They suggest that interventions that take advantage of this should be explored for their ability to enhance how effective behavioural weight loss interventions are, and how sustainable the weight loss is.

Conclusion

This small study has shown that a successful dietary weight loss programme is associated with changes in the brain’s response to images of high- and low-calorie food. Participants in the programme showed greater brain activity in one reward-related part of the brain in response to low-calorie foods, and less activity in another reward-related part of the brain in response to high-calorie foods. This effect was not seen in people who had not taken part in the programme.

There are a few things to bear in mind when interpreting this study:

- The researchers are not able to say whether the change in brain response came before and contributed to the weight changes, or whether they came after and potentially resulted from the changes in weight.

- The researchers were not able to show a relationship between eating behaviours and the level of activation in the reward centres – so they can’t say for certain that the brain changes seen were linked to changes in what people actually ate.

- The brain activity seen was in response to pictures of food rather than actual food, and this may differ.

- The groups did have different levels of dietary restraint at the start of the study, and this could influence results.

- The study was small (13 people) and a relatively short-term part of a pilot randomised control trial, so findings would need to be assessed in a larger study to see if they could be confirmed in a wider sample of people over a longer period.

- It is not possible to say whether the changes in brain activity seen are specifically related to the approach taken in the iDiet programme, or whether other dietary programmes would have a similar effect.

In conclusion, this study confirms that people can change their eating habits and weight. It also suggests that part of this may be related to changes in our brain’s “reward” response to high- and low-calorie foods. The researchers hope to use this knowledge to improve weight loss interventions, but as yet it is not clear whether this will become a reality.

For a free alternative to commercial diet plans, why not try the NHS weight loss plan.

Analysis by Bazian. Edited by NHS Choices